I just read an article by Ebony Elizabeth Thomas and Amy Stornaiuolo (Thomas & Stornaiuolo 2016) that looked at ways that young adults engage in textbending via social media. Textbending is "reimagining stories from nondominant, marginalized, and silenced perspectives" (p. 315). Thomas and Stornaiuolo argue that restorying via social media is a 21st century way for readers (who might not see their culture, gender, or other affinity group represented in literature) to engage in Rosenblatt's transactional theory of literacy, a theory that's marked by the ways a reader and a text interact.

Thomas and Stornaiuolo's focus is on young adults, and reading their article made me think of some of the ways that restorying might be applied to early reading experiences. I've often heard people explain that they don't teach critical literacy to young children because they aren't ready for the types of conversations critical literacy brings up. Conversations about gender, sexuality, race, ethnicity, ability, and more can be complicated with young children. The adult has to navigate sharing an age-appropriate amount of information while continuing to make sense and simultaneously avoid promoting one world-view over another, especially if the adult is, oh say, a teacher working with someone else's children. Talk about some tricky dance moves.

That said, my son (who is six) made up a game THREE years ago called, "Fair/Not Fair." First, he shares a hypothetical situation, then we have to decide if it's fair or not. It's his favorite game. And he likes it when it gets really tricky. And he introduces it to all his friends. And they love it. Because young children love to think about how the world works and why the world works the way it does. And that, to me, is what critical literacy does.

So, I decided that for this blog post, I would play with restorying, a tool of critical literacy, by applying it in ways that are developmentally appropriate to early readers.

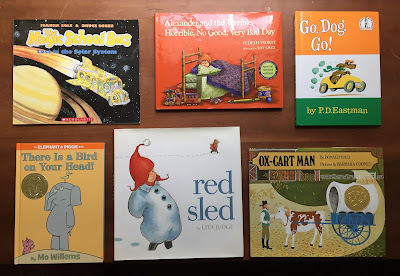

In the article, Thomas and Stornaiuolo identify six types of restorying: alterverse, transmedia storytelling, counterstorytelling, collective storytelling, alternate history, and bending. I used an incredibly scientific method of collecting books to try out with each type of restorying: I picked a bunch of my son's books off his bookshelf. Then, I played with how a kindergartener might explore each of the six types of restorying, either at the request of a teacher or independently. Results below.

Alterverse

This involves placing one character in the world of another. In order to make that happen, I needed two books. The first two books in the pile were Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day and The Magic School Bus: Lost in the Solar System. Perfect! I put Alexander in Miss Frizzle's class and imagined what would happen. Alexander wouldn’t have to cross any cultural barriers, but he would be very surprised when the bus turned into a spaceship.

This involves placing one character in the world of another. In order to make that happen, I needed two books. The first two books in the pile were Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day and The Magic School Bus: Lost in the Solar System. Perfect! I put Alexander in Miss Frizzle's class and imagined what would happen. Alexander wouldn’t have to cross any cultural barriers, but he would be very surprised when the bus turned into a spaceship.

Transmedia Storytelling

So, what did I learn from my (ridiculously long) post? First, when I applied restorying to younger literacy, the play and imagination involved felt very appropriate to an audience of young readers. Second, different ways of restorying fit different books better. I'm still frustrated by my inability to apply alternate history to Red Sled. Third, when I grabbed six books off the shelf at random in my house, four of them featured all or predominantly White characters, and five of them featured all or predominantly male characters. So, I have some work to do with my bookshelves.

Thomas, E.E. & Stornaiuolo, A. (2016). Restorying the self: Bending toward textual justice. Harvard Educational Review, 86(3), 313-338.

Thomas and Stornaiuolo's focus is on young adults, and reading their article made me think of some of the ways that restorying might be applied to early reading experiences. I've often heard people explain that they don't teach critical literacy to young children because they aren't ready for the types of conversations critical literacy brings up. Conversations about gender, sexuality, race, ethnicity, ability, and more can be complicated with young children. The adult has to navigate sharing an age-appropriate amount of information while continuing to make sense and simultaneously avoid promoting one world-view over another, especially if the adult is, oh say, a teacher working with someone else's children. Talk about some tricky dance moves.

That said, my son (who is six) made up a game THREE years ago called, "Fair/Not Fair." First, he shares a hypothetical situation, then we have to decide if it's fair or not. It's his favorite game. And he likes it when it gets really tricky. And he introduces it to all his friends. And they love it. Because young children love to think about how the world works and why the world works the way it does. And that, to me, is what critical literacy does.

So, I decided that for this blog post, I would play with restorying, a tool of critical literacy, by applying it in ways that are developmentally appropriate to early readers.

In the article, Thomas and Stornaiuolo identify six types of restorying: alterverse, transmedia storytelling, counterstorytelling, collective storytelling, alternate history, and bending. I used an incredibly scientific method of collecting books to try out with each type of restorying: I picked a bunch of my son's books off his bookshelf. Then, I played with how a kindergartener might explore each of the six types of restorying, either at the request of a teacher or independently. Results below.

Alterverse

This involves placing one character in the world of another. In order to make that happen, I needed two books. The first two books in the pile were Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day and The Magic School Bus: Lost in the Solar System. Perfect! I put Alexander in Miss Frizzle's class and imagined what would happen. Alexander wouldn’t have to cross any cultural barriers, but he would be very surprised when the bus turned into a spaceship.

This involves placing one character in the world of another. In order to make that happen, I needed two books. The first two books in the pile were Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day and The Magic School Bus: Lost in the Solar System. Perfect! I put Alexander in Miss Frizzle's class and imagined what would happen. Alexander wouldn’t have to cross any cultural barriers, but he would be very surprised when the bus turned into a spaceship.Transmedia Storytelling

Restorying via transmedia means changing the mode in which a story is told. Young readers already do this all the time when they act out stories that they’ve read. But what's a way that I could do it that would encourage restorying that engages with perspectives other than the ones already present in Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day? What if, for example, young readers studying the blues turned Alexander's story into a blues song? That would involve considering the cultural significance and historical implications of the blues and what it would mean to put Alexander’s story into that context.

Counterstorytelling

Counterstorytelling

Counterstorytelling is a way of restorying via perspective. One way to do this is to tell the story of a minor character. Next book in the pile is Go, Dog. Go! I know exactly whose story I'd love to know more about. The pink poodle with the amazing hats. I want to know what she's thinking about every time the yellow dog tells her he doesn't like her hats. I think a kindergartener would have a lot to say about that. To read an adult's take on the hats, check out this post from The Ugly Volvo.

Collective Storytelling

Collective storytelling is when readers tell a story as a group using participatory means of communication, often social media tools. By telling the story as a group, they can challenge dominant stories of how things are. And the next book is There is a Bird on Your Head.

Collective storytelling is when readers tell a story as a group using participatory means of communication, often social media tools. By telling the story as a group, they can challenge dominant stories of how things are. And the next book is There is a Bird on Your Head.

This one's kind of hard because early readers generally aren't on Twitter (get it - it's about a BIRD?!).

In the book, elephant has a problem (spoiler: it’s a bird on his head), and he only solves the problem when he speaks to the bird directly. What if each student in a class decided on something that affected him/her each day and then picked an object to represent it, and took a photo with the object on their head? Each student could narrate 1-2 sentences to an adult about what the object represented, and the pictures and text could be posted in the classroom. Follow-up might involve discussions about ways to help each other solve problems and about empathy for the things that weigh other people down.

Alternate History

This involves retelling a story with an identifiable point of divergence from the history of present reality. Red Sled is the next book in the pile. It’s a story about going a bunch of animals going sledding in the middle of the night.

Huh. This one’s particularly hard to restory with an alternate history because the story already takes place outside of present reality. Plus, every alternate history I can think of ruins the story in some horrible way.

For example, why does the young sledder live alone in a one-room house on the top of a mountain where animals have developed the ability to sled? Clearly, nuclear winter. My imagination is making the story sad.

As much as alternate histories can be totally appropriate for restorying, I think that maybe not every story can be restoried in every way.

Bending

To bend a story involves bending an attribute of a character. The next book in the pile is Ox-cart Man. This story, which narrates a year in the life of a 19th century New Hampshire farmer, is particularly well-suited for bending. What would be the details of the story if the farmer were female? If the farmer were Black? If the farmer lived in the south? If the farmer lived in a city? If the farmer had a different job? Ox-cart Man tells the poetry of an ordinary life; what’s the poetry of other people’s ordinary lives?

Collective Storytelling

Collective storytelling is when readers tell a story as a group using participatory means of communication, often social media tools. By telling the story as a group, they can challenge dominant stories of how things are. And the next book is There is a Bird on Your Head.

Collective storytelling is when readers tell a story as a group using participatory means of communication, often social media tools. By telling the story as a group, they can challenge dominant stories of how things are. And the next book is There is a Bird on Your Head.This one's kind of hard because early readers generally aren't on Twitter (get it - it's about a BIRD?!).

In the book, elephant has a problem (spoiler: it’s a bird on his head), and he only solves the problem when he speaks to the bird directly. What if each student in a class decided on something that affected him/her each day and then picked an object to represent it, and took a photo with the object on their head? Each student could narrate 1-2 sentences to an adult about what the object represented, and the pictures and text could be posted in the classroom. Follow-up might involve discussions about ways to help each other solve problems and about empathy for the things that weigh other people down.

Alternate History

This involves retelling a story with an identifiable point of divergence from the history of present reality. Red Sled is the next book in the pile. It’s a story about going a bunch of animals going sledding in the middle of the night.

Huh. This one’s particularly hard to restory with an alternate history because the story already takes place outside of present reality. Plus, every alternate history I can think of ruins the story in some horrible way.

For example, why does the young sledder live alone in a one-room house on the top of a mountain where animals have developed the ability to sled? Clearly, nuclear winter. My imagination is making the story sad.

As much as alternate histories can be totally appropriate for restorying, I think that maybe not every story can be restoried in every way.

Bending

To bend a story involves bending an attribute of a character. The next book in the pile is Ox-cart Man. This story, which narrates a year in the life of a 19th century New Hampshire farmer, is particularly well-suited for bending. What would be the details of the story if the farmer were female? If the farmer were Black? If the farmer lived in the south? If the farmer lived in a city? If the farmer had a different job? Ox-cart Man tells the poetry of an ordinary life; what’s the poetry of other people’s ordinary lives?

So, what did I learn from my (ridiculously long) post? First, when I applied restorying to younger literacy, the play and imagination involved felt very appropriate to an audience of young readers. Second, different ways of restorying fit different books better. I'm still frustrated by my inability to apply alternate history to Red Sled. Third, when I grabbed six books off the shelf at random in my house, four of them featured all or predominantly White characters, and five of them featured all or predominantly male characters. So, I have some work to do with my bookshelves.

Thomas, E.E. & Stornaiuolo, A. (2016). Restorying the self: Bending toward textual justice. Harvard Educational Review, 86(3), 313-338.

Still with me? Thanks for sticking around for such a long post!

Comments

Post a Comment